I sat through Mark Zuckerberg’s painfully stilted Meta Connect Keynote about The Metaverse pondering two questions. The first was why the team that puppet Zuckerberg’s arms are so out of harmony with those who puppet his head. His cartoon avatar was weirdly more human.

The second was why their version of a metaverse1 is so dull. Then, when the partnerships with Accenture2 and Microsoft were announced, it all made sense. Meta’s Metaverse is the VR design equivalent of PowerPoint templates and corporate design thinking spaces.

Dullness is a problem for the metaverse, because of a central paradox at the heart of VR that it appears Meta doesn’t understand. We use the word immersion to mean two different types of experiences and they pull against each other. To explain, let’s go back to 1978.

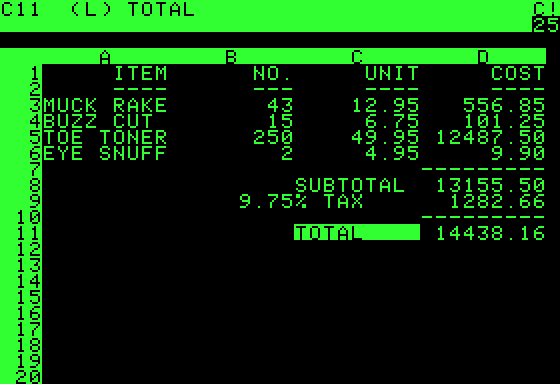

VisiCalc

This is VisiCalc, the world’s first spreadhseet, invented by Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston. Five years later, Ben Schneiderman published a paper called Direct Manipulation: a step beyond programming languages in which he described the wonder of VisiCalc and how it allowed display editors that “display the document in its final form.” Schneiderman was used to working with single-line text editors, which only allowed the user to view and edit one line at a time, “like seeing the world through a narrow cardboard tube,” he wrote in his paper. Later, he uses more recent examples from the early 80s of interfaces with rudimentary graphic elements reminiscent of early Atari games. In all of these, the key ingredient, according to Schneiderman, is that they allow users to “directly” interact with and manipulate the data to hand.

If your world was single-line text editors, it must have been a leap to see a whole calculation on one page, but obviously we look at this with modern eyes and think, “That’s not a direct manipulation interface, take a look at what I can do on my smartphone!” The thing is, hardly any digital interfaces are direct manipulation interfaces. They all use metaphors of varying levels to trick us. We’re not really pinching a picture larger or smaller on our smartphones, we’re simply wiping our fingers in a pinching motion across a piece of glass.

The clever slight of hand of the iPhone was to turn the entire device into a interactive metaphor for whatever tool you are using. Instead of it being a phone with some apps, Apple made the phone one of several apps. When you are using the phone app, your smartphone is a phone. When you’re using a web browser, your smartphone is a web browser, the same with the camera and almost all other apps. That was the conceit at the heart of Steve Jobs’s unveiling of the iPhone. It’s such a clever slight of hand that we barely notice what’s going on. We simply call it “intuitive”.

Why is it that an interface metaphor like VisiCalc can seem intuitive “direct manipulation” at one time and then 25 years later feel awkward and clumsy? We might think it is simply the processing power of modern machines, but there is a mystery at the centre of this. While many old app interfaces can feel extremely clumsy, retro videogames are still engaging. I can still buy, play and enjoy the entire Atari back catalogue on the latest Playstation. Indeed, when you play these games, you can become as immersed in the game as in a modern game like Horizon Zero Dawn. Sometimes more so, since I seem to spend a lot of time just running around in Horizon Zero Dawn a little bored.

I spent several years writing a PhD about playfulness and interactivity to try and answer this apparently simple question. The tl;dr version is that playful interfaces lead to playful interactions and we easily become engrossed in the play – we are immersed in the same way a child playing with building blocks can become immersed in the activity. These interactions don’t have to be games either, though games can clearly immerse the player through role-playing, combat, chance and vertigo – the various modes of play that Roger Caillois argued all games take in his seminal work Man, Play, Games. Most modern videogames are, at heart, either role-playing combat, competition, or mazes and puzzles.

This playful kind of immersion brings us back to VR and the metaverse. The paradox at the heart of VR is that the experience of having your senses immersed constantly distracts you from being immersed in the content.

Occasionally in TV shows or movies, you would see the boom mic drop in from the top of the frame. These days you might spot a coffee cup or water bottle in the background of a historical film. This immediately breaks your willing suspension of disbelief—the idea that you know a film or theatre play is not real, but willingly pretend it is in order to enjoy it3. It pulls you out of the immersion of the story or game.

The same happens when games are glitchy or have janky controls4. VR does this to you all the time, even when the graphics are pretty smooth and high quality. There’s no getting around the fact that, despite the illusion, part of your brain knows you’re wearing a headset. It’s worse if you wear spectacles like me. Apart from often getting headaches, it always takes me about 5-10 minutes for my eyes to get back to normal focusing afterwards.

Now, there is compelling VR content. Some of it uses clever illusions that do trick your brain into believing you’re there, though actual physical reality brings it into check pretty quickly. What you’ll notice in this kind of content is how much effort goes into convincing you you’re in a real space. Games are, of course, great at this—the gameplay is compelling content. But here’s the thing: compelling content is not enhanced by VR. Compelling content helps overcome the constant physical reminder that you are in VR. It’s the content that helps you suspend your disbelief, not the technology.

From Zuckerberg’s keynote, it appears that Meta see success in VR as a technology issue to be solved. Better, lighter headsets may indeed help with the distractions of physical immersion, but I see plenty of people deeply immersed in the tiny, flat square of glass of their smartphones. Immersion is not a VR technology problem, it’s a content problem. That’s why boring scenarios in VR are a non-starter and there’s nothing more boring than meetings, the prime use-case examples from Meta and co.

Yes, there are occasions in which work meetings in virtual space might be useful, compelling even. Workshops, perhaps. Walking around objects or data in different dimensions, like studying molecular structures or moving through some data visualisation, maybe. Yet these are not the scenarios Meta is envisaging. In their virtual world, people inhabiting their LEGO-friends style avatars in a tasteless corporate meeting room meet with others who can’t be there in VR streamed onto a 3D rendering of a boardroom video conferencing set-up. Yawn.

Yes, you can work this way in VR, but why would anyone possibly want to? People turn their cameras off on group calls to tune out and check their e-mail. Hell, I’ve tuned out in plenty of real-life face-to-face meetings. Why would anyone want to don a headset to sit in a virtual conference room pretending to video chat with someone? The same goes for using a spreadsheet on a virtual screen. Sure, it’s possible in VR. I might fill half my luggage with a VR headset so I can have wrap around VR monitors in my hotel room, but I probably won’t. I have a smartphone in my pocket and a laptop in my backpack and I’ll use those. Excel’s UX is awful as it is, I don’t want to add to that.

What was missing from Zuckerberg’s keynote was imagination and creativity. Why are these people not having a meeting in the forest of Zuckerberg’s avatar hair or wandering around the arteries from a patient’s 3D rendered medical scan or even simply having a meeting outside under the oldest tree in the world instead of in an ugly conference room?

This doesn’t even begin to touch upon the most compelling content in virtual worlds – other people. The other place we talk about being immersed is in conversation. As Mark Pesce and Tony Parisi explain in their must-listen series, A Brief History of the Metaverse, it’s not enough to just make a world and let people inhabit it and all will be well. That’s what Second Life tried and all is not well there. People need a reason to be the space and to interact and that’s the other reason games are so compelling. Fortnite’s Battle Royale storm that forces randomly dropped players together is a brilliant mechanic for this.

Office work is not a compelling reason to meet in a virtual space. If we’ve learned anything in the past two years, it’s that office work is only seldom a compelling reason to meet in real-world space. Like so many folks in tech, Meta appear to view the history of the medium as worthless. No wonder they’re doomed in their repetition of it.

This post was originally part of my newsletter Doctor’s Note. Sign up if you’d like to receive more of my writing and a whole host of links and reading suggestions.

-

I’m using capitalised “Metaverse” for

Facebook’sMeta’s branded version, but metaverse for the general concept, since Neal Stevenson came up with the name. ↩︎ -

Disclaimer: My previous employer. ↩︎

-

A phrase coined by 18th Century poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge ↩︎

-

If you really want to understand the relationship between immersion and janky games controls, Janky Controls and Embodied Play: Disrupting the Cybernetic Gameplay Circuit by M. D. Schmalzer is a great read. ↩︎