AI-generated and mixed realities are blurring the boundaries of “truth” and challenging how we value it. Synthetic Realities have reached new heights of sophistication, sparking controversy, and also fascination, about its creative possibilities. The mixture of fear and fascination of the power of synthetic media is understandable, but wrongly frames its future trajectory.

The technology behind synthetic media has developed enormously over the past couple of years and in varying forms. In the months between researching the Synthetic Realities trend and writing this essay, the resolution and accuracy has increased so fast that I have had to constantly go back and edit the text to keep up.

The essay is a long read full of links and media embeds. One reason for this is to counter the clickbait headline and bite-sized article trend and spend the time unpacking an argument and tracing the historical threads. There is still a pleasure to be had in the long read. The other reason is because I wanted to gather all the material in one place. It is not until you see it all together that you have the moment of realisation that the creative industries are about to change as radically as when Photoshop and 3D animation arrived on the scene.

Let’s get started with some well-known synthetic media examples.

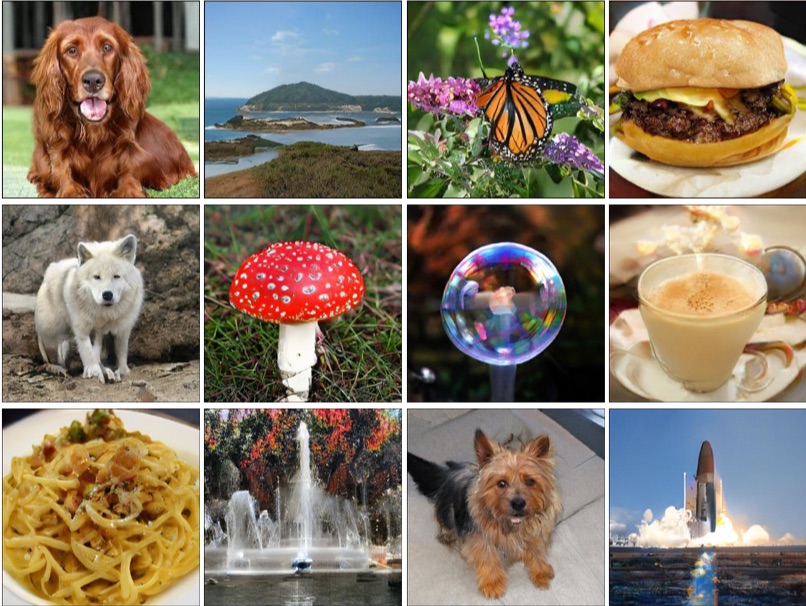

There is no spoon

Nothing above is real. They are all generated images from bigGAN. (Source).

None of the pictures above is real. They have all been generated via Generative Adversarial Networks or GANs. Pioneered by Ian Goodfellow and his team, GANs are a form of AI machine learning that pits two neural networks in against each each other to evolve synthetic images.

This technology has become most well-known through the rise of deep fakes, a particular use of GANs to swap the face of one person onto another, giving the appearance that the person has done or said something they never did. They originated on Reddit via a user using the handle “deepfakes” who initially showed off how he could swap the faces of Hollywood actresses onto the bodies of porn actresses. The porn industry having always been the traditional early adopter of new technologies.

Others soon started experimenting with them and Nicholas Cage became the preferred subject, thanks to his movie, Face Off. More recently, YoutTuber Ctrl Shift Face created a face swap of Bill Hader and Tom Cruise. Hader does an impression of Cruise and his face subtly switches to Cruises. Keep and eye on his teeth, which switch from regular guy teeth to Tom Cruise beamers (it starts around 0:54):

Bill Hader switches into Tom Cruise

Filmmaker Jordan Peele brought the face swap technology to mass attention with his 2018 Obama PSA video on Buzzfeed, stressing the dangers of this kind of material in a post-truth, fake news world.

A wave of other articles followed and there has been a mixture of fear and fascination about the power of synthetic media to distort public discourse and democracy. The fears are understandable and bear consideration, but by ignoring history, they wrongly frame the future trajectory of synthetic media, which stands to change the world of creators far more than that of viewers.

Jordan Peele’s fake Obama PSA for Buzzfeed

The concerns about deep fakes in the current context of fake news overstate the technology of the visual and overlook the role of storytelling. A more useful way of understanding synthetic realities is not as something entirely new, but the latest iteration in a long history of fakes, hoaxes and propaganda, ranging from jokes to manipulating perceptions of history.

Fake olds

One of the earliest and most famous digital image manipulations that might be considered “fake news” was in 1982 when National Geographic moved one of the Pyramids at Giza so that the landscape picture of the camel train passing in front of the pyramids would fit their portrait format cover. They used a very expensive high-end system from Scitex to do so.

National Geographic was rightly chastised by their readership and scientific community, who felt a scientific journal should not be altering “reality”. These days National Geographic own their early mistake and use it as an important example of the ethics of image usage.

At the time, however, National Geographic’s Editor, Wilbur E. Garrett, claimed it was not falsification, “but merely the establishment of a new point of view” in an eerie premonition of Kellyanne Conway’s “alternative facts" assertion.

Garrett’s defence is not as outrageous as it now sounds. Magazine and newspaper editors and photographers have cropped, toned, re-framed and juxtaposed images for dramatic and editorial effect for decades. Framing is part of the art of photography, as is cropping and image adjustment when printing photographs.

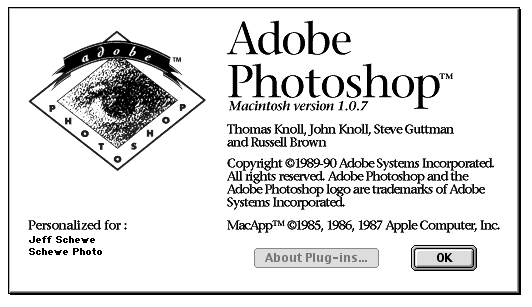

Just five years later, in 1987, the application that became Photoshop was developed by the Knoll brothers, launching commercially as Photoshop in 1990.

Photoshop 1.0’s splash screen - Image: photoshopnews.com

The dates above are not just a historical footnote. They show the pace of change. In just ten years the technology went from enormously expensive specialist technology to mainstream desktop application.

The first version I ever used was Photoshop 1.0.7 around the beginning of 1991. Cutting a pasting parts of an image was suddenly effortless compared to analogue photo printing. The clone tool that allowed you to copy a portion of the image and paint it elsewhere simply felt like magic.

Photoshop changed the world of photography and digital image manipulation forever. Like all technologies intrinsically linked to Moore’s Law, the pace of change exponentially increases. The selfie-improvement and filter algorithms in smartphone apps like Snapchat, Facebook and Instagram all owe their origins to Photoshop. What used to take hours of processing is now done in real time, on live video.

The recently viral FaceApp and Zao apps, do most of their AI-driven processing in the cloud and send back the modified image — the hardware in your hand isn’t quite powerful enough yet. It’s the data transfer and rights agreement that sent the Internet into a meltdown, not so much the processed images. It’s also worth remembering that the first iPhone couldn’t even shoot video, a fact that feels almost unbelievable today.

Hoaxes and propaganda

Hoaxes and propaganda have a long and dishonourable history in photography. The Bronx Documentary Center’s Altered Images project has an excellent collection of media images of this kind.

The list of political image manipulation for propaganda and censorship is long. Stalin and Hitler are both renown for retrospectively removing people who had fallen out of political favour from photographs.

Stalin’s censors remove water commissar Nikolai Yezhov (who was arrested and shot). Image: Wikimedia.

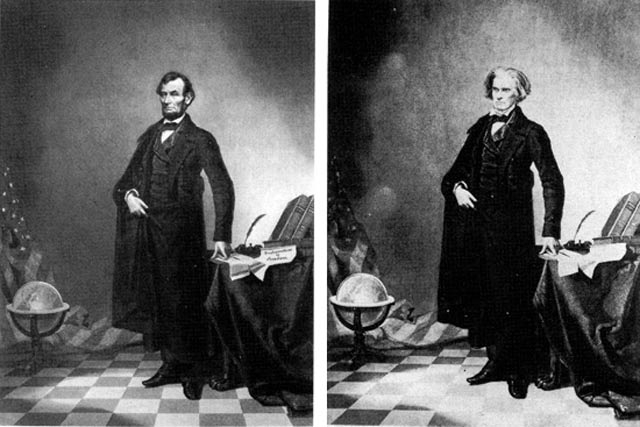

Even the iconic lithograph portrait of President Abraham Lincoln uses Lincoln’s head composited onto Southern politician John Calhoun’s body.

Lincoln’s famous portrait is a composite. Image: http://www.famouspictures.org

Australia’s Prime Minister John Howard famously won the 2001 general election on a “strong on border protection” platform relying heavily on selected and sometimes cropped images of asylum seekers’ children in the water, falsely claiming they had been thrown callously overboard by their parents in what is now known and exposed as the “children overboard affair.”

Political media narratives around asylum seekers have not changed much in the 18 years since.

The power of storytelling

The combination of storytelling and doctored images goes back to the very early days of photography. The 1917 Cottingley Fairies hoax is one of the most well-known.

Two cousins, Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright borrowed Elsie’s father’s camera and created a set of photographs showing them at the bottom of their garden surrounded by tiny fairies. Their father developed the photos and dismissed them as a joke, but Elsie’s mother, Polly Wright, was part of the spiritualism movement of the age and showed them to the speaker at a lecture on spiritualism she attended.

Via the leader of the Theosophical movement, Edward Gardner, the photos ended up being examined by a photographer called Harold Snelling. Snelling judged them to be:

“[G]enuine unfaked photographs of single exposure, open-air work, show movement in all the fairy figures, and there is no trace whatever of studio work involving card or paper models, dark backgrounds, painted figures, etc."

They seem obvious fakes to us now, but the technology was relatively new and, crucially, Polly Wright, Edward Gardner and Harold Snelling wanted to believe them to be real.

Pulling on this historical thread unravels the historical tangle of technology, storytelling, propaganda and culture that stretches back into prehistory. The story every British schoolchild learns about the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and King Harold’s death by an arrow through the eye, as depicted by the Bayeaux Tapestry, is most likely fake news spread by the Normans to legitimise the their invasion of Britain. History is, indeed, written by the victors—it is the original fake news.

From the ancients to Norse sagas, influencers to Trump tweets, we use stories to shape our narratives of success, failure, place, meaning, beliefs, ethics and values. Stories become legends, legends become myths. Tracing these all the way back we end up, as psychoanalyst C.G. Jung did, at the ancient mythological archetypes that underpin our understanding of our place in the universe.

Of course, the extreme view from the likes of Elon Musk is that all human life is, in fact, a simulation. There has also been ongoing debate amongst gaming scholars about whether virtual reality is a genuine reality or a fiction.

Mislabelling and media forensics

Law professors, Bobby Chesney and Danielle Citron‘s paper, Deep Fakes: A Looming Challenge for Privacy, Democracy, and National Security dives deep into the potential threats of deep fakes, but their hypotheticals have already happened in one form or another. The technology of deep fakes is largely irrelevant to the argument. Mislabeling and misattributing imagery is the quickest route to spreading propaganda and misinformation, especially in the days of social media sharing, where stories are barely read, let alone fact checked, before being shared.

The furore over the social media distribution of doctored videos of Nancy Pelosi, slowed down to make her seem as if she is slurring her speech, is a recent, high profile example. There is no sophisticated GAN at play here, just speed shifting a video. It seems relatively obvious that the video is slowed down, but if you want to believe Pelosi has medical problems or is drunk, then it fits your internal story just fine. Confirmation bias is always thirsty for good stories to fuel itself.

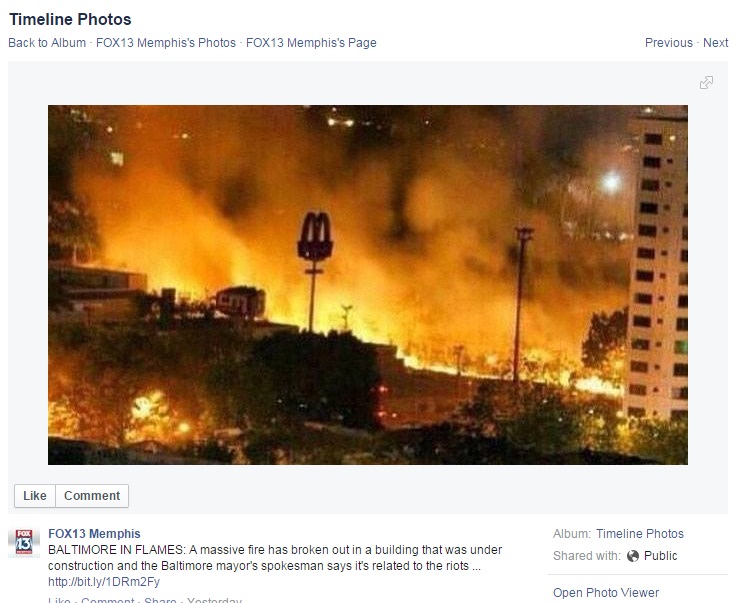

The Altered Images project has a whole host of these examples. One is from FOX13 who posted a picture on their Facebook page with the caption, “Baltimore in flames” and the description: “A massive fire has broken out in a building that was under construction and the Baltimore mayor’s spokesman says it’s related to the riots…”

FOX13’s mislabeled news image. (Source)

Altered Images explains the real story behind the photo:

“The photo was taken in Venezuela a year prior. A user on Imgur, a comment-based online image hosting service, exposed FOX13 Memphis’ mistake two days after the original posting.”

The story and the label is the fake news, not the image or the image technology behind it. The real issue is the platforms that help misinformation spread so quickly and our culture of diminished attention, as Mark Pesce so cogently argues in The Last Days of Reality:

“The future of power looks like an endless series of amusing cat videos, a universe cleverly edited by profiling, machine learning, targeting and augmented reality, fashioning a particular world view in which we will all comfortably rest. That’s already the case for billions of Facebook users, a lesson widely noted by those in power, carefully studied and soon to be widely copied. Facebook has been the beta test for a broad assault on all reality. As these techniques become universal, with the world now listening to us, then adapting to our wants and whims, while subtly shaping us to its ends, we lose our moorings and become entirely post-real.”

Nevertheless, the rising concern about synthetic media being indistinguishable from “real” media has led U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to set up a media forensics program. The same GAN technology behind deep fakes is also used to spot them, often finding small artefacts in the image or noticing that the generated face doesn’t blink often enough (because the training data has far fewer frames of faces with their eyes closed). Meanwhile, Adobe has been collaborating with UC Berkeley to detect facial manipulations in Photoshop. Other tools exist to detect altered images based on differing JPEG compression artefacts.

We can expect to see more of these systems and a technological arms race between the generating and forensic tools. These will matter when it comes to using images as evidence in a court of law. They may prove to be irrelevant to everyday consumers of media responding to the story as they wish.

The cultural norming of technology

“There is nothing so amazing that we can’t get used to it.” – Ian McEwan, Machines Like Me

While the developmental pace of synthetic image technology can feel worrisome, it is how quickly technologies that are both entertaining and useful become normalised in culture that shifts the ethical boundaries most rapidly.

In less than two decades, digital image manipulation became so normalised that “Can’t you just Photoshop it?” became a stock phrase, much to the chagrin of many a designer. Photoshop has become a verb (to Photoshop something) and an adjective (it’s a Photoshopped image) — the true sign of mainstream cultural absorption of a brand and technology, like Hoover and Sellotape.

In less than five years, talking to an AI-assistant, such as Alexa, Siri or Google has become normal. During the writing of the Fjord Synthetic Realities Trend, I had an interaction with my Google Home where it failed to continue the context of the conversation and suddenly switched from omniscient being to stupid robot.

Like the boom mic dropping in from the top of the screen in a film or a typo on a page it derailed my willing suspension of disbelief. I was suddenly aware that, up until that point, I had been happily having a “conversation” with the Google Home, not pretending to have a conversation. As godfather of AI, John McCarthy famously said back in 1955, “As soon as it works, no one calls it AI anymore.”

We can expect the same of AI-generated imagery. It will become quickly normalised, as will the tools that generate them. I recently showed a German friend of mine the news footage of Angela Merkel having one of her recent attacks of the tremors. Her immediate response was disbelief and, “No! That’s just one of those fake video things.” This is someone who is not particularly across the latest technological developments, but spends enough time on social media to make that assumption.

The “cultural forensics” question is whether our ability to “read” synthetic images as synthetic will keep pace with the technology that creates them. The societal question is not whether people will believe deep fakes, but whether people won’t care and will stop believing anything in a kind of truth nihilism. I suggest this has already happened in large swathes of political and media discourse (social and mainstream). That has been the triumph of fake news.

The most likely harm will come from the use of deep fakes to harass people online, such as journalists, politicians, celebrities, revenge porn and social media bullying. Again, this is not intrinsic to the technology of synthetic media. Carole Cadwalladr, the journalist who broke the Cambridge Analytica scandal, was harassed by her powerful opponents, often with very low-tech videos of her face crudely cut and pasted onto another’s body.

What deep fakes do make easier is the ability to do this at scale and with easier automation. That synthetic media harassment still needs a platform to exist upon for it to spread, however, and, as we’ve seen, those platforms are reluctant to combat the issue.

Most recently, a cloned voice—what AI startup Modulate call “voice skins”—was used to fraudulently pose as the German CEO of an energy company and persuade the UK CEO to transfer €220,000 to the bank account of a fake Hungarian supplier. Although it uses synthetic media, the scam is really one of social engineering and a failure of corporate culture to challenge authority. Social engineering is all about the stories.

State of the art

So where does all this leave content creators? Let’s take another step back in history, this time looking at the use of computer generated imagery (CGI) in cinema.

In 1993, Jurassic Park was the most ambitious cinematic piece of CGI to be seen on film. These days we can easily read the dinosaurs as CGI (have a look at the original trailer), partly helped by the fact that we know the dinosaurs cannot be real. Despite the incredible artistry of the time, the lighting and compositing are still slightly off, compared to the live action. But the story draws us in and, like all stories, we suspend our disbelief for the duration. The same was true even back in the early days of visual effects in film, because story is king. (It was the English poet [Samuel Taylor Coleridge](willing suspension of disbelief) who coined the term “willing suspension of disbelief” way back in 1817.)

The first digital face-swap in Jurassic Park, 1993

A lesser-known piece of CGI history is that Jurassic Park included the first digital face swap. In the scene in which the young girl, Lex, is chased by the velociraptor into the air duct and nearly falls back down, the stunt double looked up. Instead of re-shooting the scene, the digital effects team at Industrial Light and Magic mapped the face of the actress, Ariana Richards, onto the stunt double’s face. It’s only about 12 frames and barely perceptible, even if you know.

Jurassic Park, 1993. Did you spot the original stuntwoman’s face just before the face-swap?

Jordan Peele’s 2017 video actually required quite a lot of traditional post-production in Adobe’s After Effects, but soon techniques emerged to do much of this in real-time, either via the lip-syncing synthesis technique or via facial reenactment and Deep Video Portraits.

Deep Video portraits

In their paper, Chesney and Citron note of the use of facial reenactment in the recent Star Wars movies:

“The startling appearance of what appeared to be the long-dead Peter Cushing as the venerable Grand Moff Tarkin in 2016’s Rogue One was made possible by a deft combination of live acting and technical wizardry. This was a prominent illustration that delighted some and upset others. The Star Wars contribution to this theme continued in The Last Jedi, when the death of Carrie Fisher led the filmmakers to fake additional dialogue, using snippets from real recordings.”

The resurrection of Peter Cushing for Star Wars Rogue One

Knowing the many thousands of dollars that were spent to re-create Peter Cushing and Carrie Fisher’s performances, what was more astonishing was how quickly deep fake enthusiasts made their own version, with equally good results (though lower resolution) using a desktop PC.

A deep fake version of the young Princess Lea scene in Rogue One. Original footage is the top one.

The lure to live forever on screen has led to several actors having themselves digitally scanned for future visual effects and post-death appearances. For large franchises like Star Wars, the lead actors are always scanned just in case they’re needed in the future. It’s a practice that has been going on for some time.

It is this combination of cultural normalisation and the pace of development of everyday tools that poses the greatest disruption for content creators, far more than that of content consumers. Let’s take a look at where we are currently at and what it might mean when all these come together.

GAN variations

Deep fakes make use of crossing the inputs and outputs of GAN training networks to swap faces. CycleGAN and StyleGAN makes an art of this by mapping the style of one input and applying it to another, as in these examples of a horse being turned into a zebra, flowers taking on the style of another flower or applying an artist’s style to a landscape photograph.

A horse to zebra style swap using cycleGAN

Although impressive, the initial low resolution and artefact errors in these seems fairly unchallenging, until you compare how they have developed in the space of just a few years.

4.5 years of GAN progress on face generation. https://t.co/kiQkuYULMC https://t.co/S4aBsU536b https://t.co/8di6K6BxVC https://t.co/UEFhewds2M https://t.co/s6hKQz9gLz pic.twitter.com/F9Dkcfrq8l

— Ian Goodfellow (@goodfellow_ian) January 15, 2019

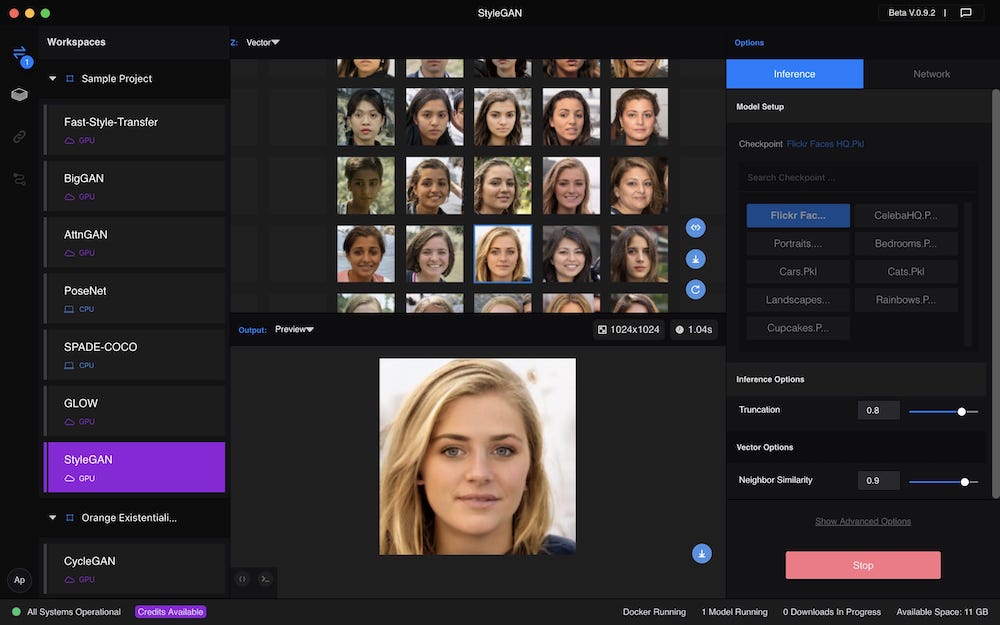

The Nvidia team behind StyleGAN increased the resolution remarkably and with their 2018 paper they published an impressive set of AI-generated images of people, bedrooms and, of course, cats. Notably, they showed interpolations between different style variables, such as gender, race, hair, eyes, pose, expression, and even glasses.

StyleGAN video demonstrating the range of detail controls

So now we have the ability to generate high-resolution, highly believable images of pretty much any kind of person we want. And cats and bedrooms.

It is not clear from the research paper whether the slider interface is a reverse-engineered illustration of the internal mechanics or whether it is an actual interface. In any case, this will be one of the UX and UI challenges facing designers and it raises plenty of questions.

What should the interfaces of these systems look like and what might be the ethical and diversity implications of these decisions? Should we just let the AI render what it considers to be the image for the context, based on the data it has or should the content creator decide?

Should it match the viewers preferences, if so, should we let them know and how? Will these kinds of notices become as ubiquitous and tedious as GDPR cookie notification and ignored?

A synthetically generated face using StyleGAN in Runway ML

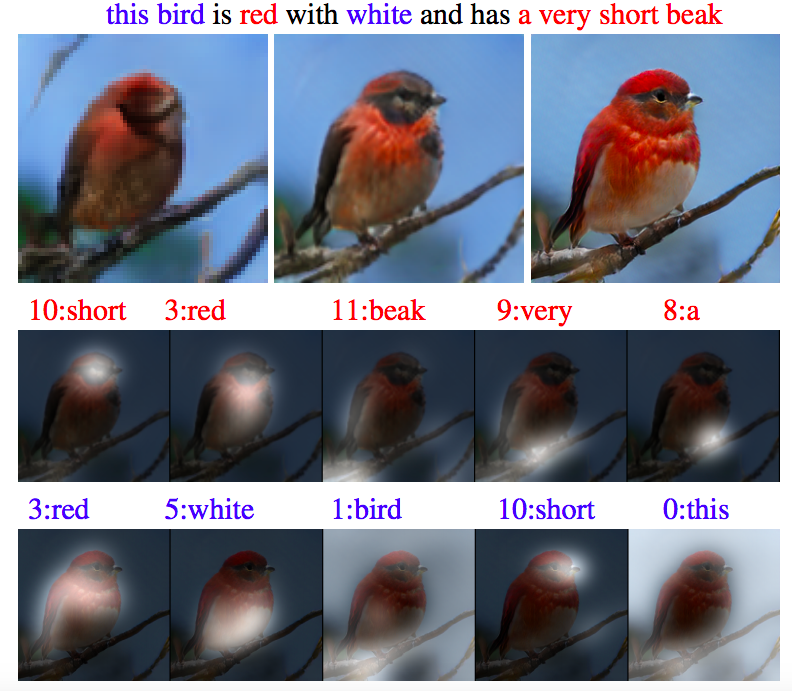

If you’re in the business of advertising, marketing and communications. photography and fashion, your world is about to change dramatically. StackGAN and the follow-up AttnGAN can synthesise photorealistic images from text descriptions.

A bird generated from a text description

“A red and white bird with a very short beak” or “a photo of homemade swirly pasta with broccoli, carrots and onions” gives you a picture of exactly that. They are partially built from reversing engineering the learning behind Caption Bot and Seeing AI, both of which describe images in text.

Strike a pose

Vue Model’s virtual model technology. Image: Vue Model.

Vue Model generates on-model fashion imagery from a photo of the garment. It can alter the pose and skin colour of the model, effectively being able to generate hyper-personalised catalogue images.

Data Grid, a startup based at Japan’s Kyoto University, are slightly more advanced with their system to generate head-to-toe fashion models, including the clothes at very high fidelity. Here is a sample of models, clothes and poses:

Data Grid’s head-to-toe fashion models

So, now you no longer need the expense and effort of a photographer and models. But why stop there? AI-generated fashion already exists. GLITCH founded by computer scientists turned fashion designers Pinar Yanardag and Emily Salvador at MIT also generates unusual clothing that the team then make real.

Then there is the strange world of virtual fashion in which people with too much money and a sustainability conscience have started to pay for digital clothes. These are clothes that never exist beyond a bespoke rendering on a photograph of you to post on Instagram.

Synthetic people in synthetic worlds

Lil Miquela at the beach. Do synthetic people need sun protection?

Given the rise of virtual Instagram influencer Lil Miquela (who currently has 1.6m followers) and her forays into music, advertising and interviewing, it seems likely that the first full GAN-generated artist is around the corner.

Lil Miquela is actually the brainchild of Brud, a “a transmedia studio that creates digital character driven story worlds.” So transmedia that their website is a Google doc. And, as we’ve seen, compelling stories cultivate the suspension of disbelief.

There are two important thing to understand about Lil Miquela in the context of synthetic media. The first is that people are quite happy to suspend their disbelief and engage with her. Reading the comments on her Instagram account it seems that about half the people are playing along, but there are plenty of comments that appear to take her as a real person. It’s hard to tell, since Instagram itself is often so synthetic.

The second is that she’s also a product of social media influencer culture. The key to being an influencer is not necessarily being able to do anything, but to cultivate a following simply by telling stories about your daily life, however manufactured those stories are. (Most big influencers—and teenagers—have a secret account, called a Finsta, for their real friends). This is fertile ground for a story-driven, synthetic personality.

Lil Miquela is currently 3D-rendered, not live AI-generated, but the next stage is already on its way.

The Dalí Lives exhibition at the Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, used machine-learning to generate the videos. They used a voice actor and also mapped the face onto the body movements of a real physical actor, but the face is AI-generated, not 3D-rendered. The installation uses pre-rendered rather than realtime video, but there is a telling cultural moment in the video when Dalí breaks the fourth wall and takes a selfie, turns the phone around and shows the photo of the visitors with him in front. It obviously feels like a magical experience.

Behind the scenes of Dalí Lives.

From simple shapes to street scenes

Part of the challenge of synthesising people and worlds is that the GANs need vast amounts of training data. When generating something new, it’s useful for them to have some guidance as to what should be generated.

Street journey generated through semantic label mapping. (Source)

Semantic label mapping uses abstract colour blocks, coded with labels (purple for cars, green for trees, for example) and generates synthetic images and videos from them. This makes it easier to generate a photorealistic world, people and animals from basic shapes, which are simple to generate procedurally.

Video-to-Video synthesis

Imagine the simplistic shapes of a mid-90s Super Mario world being rendered this way. Actually, you don’t have to, because Jonathan Fly already did:

Mario World 1-1 with #GauGAN, now with better frame-to-frame consistency. I used the flower category for the clouds.

— Jonathan Fly 👾 (@jonathanfly) August 6, 2019

@NVIDIADesign #SIGGRAPH2019 pic.twitter.com/U8X4LpY1bQ

Here’s Fly using one of my favourite old arcade games, Pole Position, as the source to synthesise a track via GauGAN:

Pole Position, now with added GAN

Returning to our synthetic artist, the dance moves are already easily generated. The example below uses a source video to capture dance moves and generate a semantic map, in turn used to generate a synthetic person dancing.

Pose to Body generating a new dancer. (Source)

Talking the large dataset training issue, the Few-Shot Adversarial Learning of Realistic Neural Talking Head Models research synthesises remarkably realistic renderings based on just a few frames of a persons face to set the “landmarks.” The team even applied it to single frames, bringing some classic images of Einstein, Marilyn Monroe, and even the Mona Lisa to life as “living portraits.”

The Few Shot talking head of Mona Lisa and other dead celebrities

If we pull together synthetically-generated people wearing synthetically-generated fashion with the ability to synthetically clone voices (Accenture and Rothco used this technology for the JFK Unsilenced project) and an AI-driven text generator, such as GPT-2 from OpenAI you largely have all the ingredients of complete synthetic artists. They may even use their own synthetic music and conjure up their own synthetic environments.

Hatsune Miku

If you’re thinking that this is unlikely to go mainstream, consider that Hatsune Miku is a Japanese “artist” who doesn’t exist. She is a Vocaloid software voicebank. The first version of her was created back in 2007 and she reportedly has 100,000 unique songs to her name. Here she is performing in front of thousands of fans “live”:

Hatsune Miku singing her hit ‘World is Mine’

Deceased rapper Tupac was digitally resurrected for a similar performance at Coachella in 2012. The “hologram” is actually a very old theatrical technique called Pepper’s Ghost).

Tupac’s Coachella resurrection

One might argue that Hatsune Miku or the Tupac performance is obviously fictional and rendered and therefore less “dangerous” than a deep fake. Lil Miquela blurs those boundaries of media and culture further making such a judgement less clear. Crucially, the fact that either of them are synthetic makes little difference to the audience experience of them. The fans at the Hatsune Miku concert sing along just as they would with a real performer.

The same is true of politics and the media. We have already passed the point where people believe what they want to believe and reject anything else as fake. Does adding more fake to fake make it any more fake? Walter Benjamin might have argued that the endless replication of the fakes across social media actually makes them more real as cultural icons.

As if embracing this point fully, the Chinese state-run press agency, Xinhua has rolled out AI-driven news anchors developed together with Sogou. They launched with one in November 2018, but they recently got upgrades with their female anchor and a male full-torso one for added gestural communication.

The nice thing about AI news anchors is that they’ll say whatever you want them to say, of course.

Synthetic media and the future of design

So far we’ve mostly looked at tools that run in development environments to synthetic media. This is reminiscent of the early days of most popular technologies, from cameras to the Web. They start in the hands of specialist technicians before being given more accessible affordances.

The rise of blogging via services like Blogger.com and “Web 2.0” or the “read/write Web” that gave rise to social media are both examples of how this shift democratises media creation. Desktop publishing followed a similar path. Usually there is a period of experimental chaos, followed by the emergence of new disciplines and design patterns, before moving into a period of stability (often marked by a certain sameness).

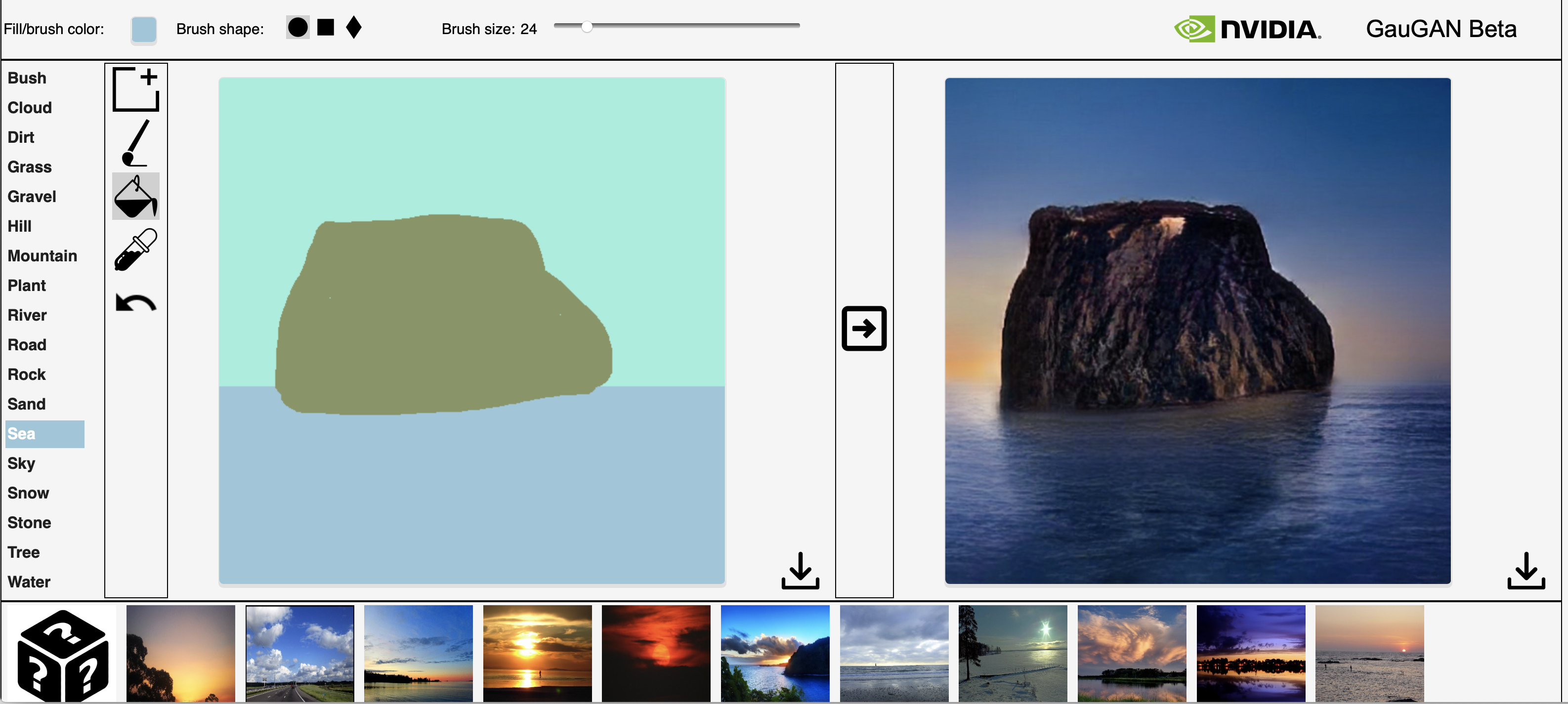

An image generated from my sketch on GauGAN.

One of the biggest spaces for designers to play a part is in designing the tools themselves. Up until recently, they have been experimental prototypes with crude interfaces. For example, GauGAN is a tool that allows you to do this with still images – you can play with it yourself on Nvidia’s AI playground site. It also uses semantic label mapping to turn a kind of Microsoft Paint blobby picture into a AI-generated landscape, almost rendered in realtime.

Adobe’s Content-Aware Fill in After Effects - Image: Adobe

Although GauGAN is pretty basic, the resolution and accuracy are increasing rapidly. Some of the underlying technology is already present in Adobe’s new tools, such as Content-Aware Fill in Adobe After Effects. Another new tool, recently made available as a public beta, is Runway ML. It is a complete application bringing many of the machine-learning examples described in this essay into an intuitive interface requiring no coding skills at all.

Adobe’s Content-Aware Fill and Runway ML’s application essentially allow you to generate the environment or people of your choice for your project. After all, once you’ve removed the undesired elements from your reality, why not add some new ones in? Or swap some faces, since that’s the current trend.

Spontaneous serendipity is of the points often used to argue that the creative industries are less susceptible to replacement and disruption by AI and automation. But that takes a view of AI as robots, mindlessly performing repetitive tasks. By contrast, GANs can be rather wonderfully weird, especially while in training mode. In the hands of artists like Mario Klingemann they can produce some remarkably unusual imagery.

Cat Face [my title] by “squishybrain” on Ganbreeder

If you are in the business of creating slightly surreal illustrations, GANbreeder does a pretty good job. It’s a tool that allows you to breed different images together to generate new ones, over and over. You might even have them printed and framed.

UX and UI design

The above examples give the impression that AI is best applied to pixel-based images and video when it comes to generating media. It is certainly a strength of GANs, especially when generating highly believable images of people. However, AI can also generate code from pictures and the reverse, code to images.

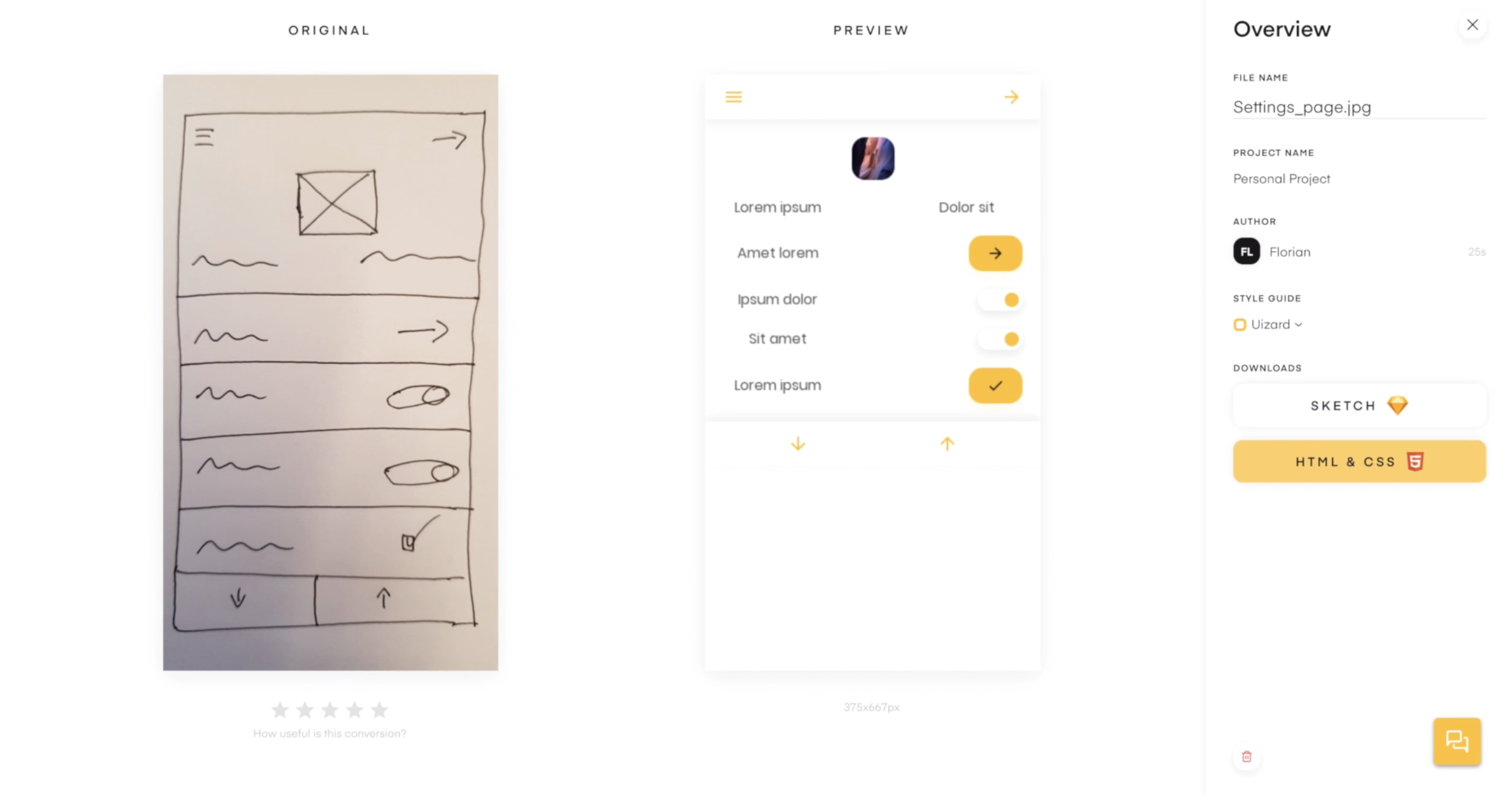

Pix2Code is a project that generates code from a screenshot of a GUI. The result is a fully editable UI project. This required teaching AI to understand user interfaces.

Having achieved this, it’s now possible to generate UI projects from sketches, which is where Tony Beltramelli’s research has ended up as the platform UIzard. UIzard now generates HTML and CSS from your sketched wireframes and integrates with Adobe XD and Sketch.

UIzard understands wireframe sketches and turns them into Sketch files and code

A/B testing works somewhat similarly to a Generative Adversarial Network. The generative network of your design team generates material and the discriminative network of the test participants that evaluates them. Some companies already do this at massive scale, of course. Mark Zuckerberg said there are around 10,000 versions of Facebook running at any one time, as engineers test ideas, while Amazon famously pushes code live every 12 seconds and can test a feature on 5000 users by turning it on for just 45 seconds.

But testing one feature at scale is vastly less complex that multivariate testing of features, which can run into hundreds of thousands of combinations, which is where AI-driven A/B testing using evolutionary computing algorithms comes into play.

Questions, decisions and ethics

So, now, we’re nearly at the point where AI can synthesise imagery and content (with tools like GPT-2), generate and test the UI and content at scale. What will it mean for the role of designers if we move beyond design systems and Design Ops and there are 100,000 versions of a user experience out there?

Let’s recap. We can now:

- Synthesise people, faces, objects, animals

- Capture and re-generate poses and movement

- Modify facial expressions

- Synthesise places and landscapes

- Clone voices

- Generate completely new imagery

- Generate writing

- Effortlessly erase anything from images/video

- Generate GUIs and UX flows

- Link them all together in design workflows

As with other fields of design, the AI+human blend is likely to also be the future role of many designers, guiding, curating and pruning the inputs and outputs of AI-generated content rather than creating it from scratch themselves.

Then we have the ethical implications of all those different versions of photography and illustration. On the one hand, it enables inclusion and diversity, as we discussed in the Inclusivity Paradox Fjord Trend. Each person sees their own custom version of content that uses their language and tone of voice, with (synthetic) photography of people who look like them, and with a user experience uniquely tailored to their needs and desires. You can see how attractive this might be to brands and how consumers may start demanding it.

On the other hand, it may reinforce our social media echo chambers if we only see people like us. When these personal synthetic media are driven by micro-targeting, what is presented may also end up simply wrong or offensive. What happens when the AI-generated image looks by chance exactly like a recently deceased loved one, just with the wrong hair?

As designers, we might have no idea that it is happening or why. We would have to pore over the data patterns to try and solve algorithmic anomalies and errors. This will raise the importance of data designers working with developers.

Expression modification

Apple’s FaceTime Attention Correction algorithm adjusts the position of your eyes to make it look as if you’re looking directly at the person you are calling rather than at the screen, because it’s natural to look in the eyes of the person on screen rather than at the camera. Andrew O’Hara, writing for AppleInsider notes:

”The whole thing looks very natural and no one would likely even notice without prior knowledge of the feature. It simply looks like the person calling is looking right at you, instead of your nose or your chin.” [Emphasis mine]

The user can turn it on or off, but does that mean I can pretend to pay attention even when I’m not? Is that okay? What about cultural situations in which staring directly at someone while they are talking is threatening or disrespectful or changes the perception of the conversation?

If I’m doing that, could I correct for the lens distortion, because the selfie lens makes my nose look big? Maybe I’d like to add little bit more smile, because my resting face looks grumpy (mine does)? And remove that spot on my nose or make me look a little less hungover, because it’s a FaceTime call for a job interview.

Changing your emotional expression in real-time using cycleGAN

Whilst I’m there, I’d like to sit in front of an synthetically generated room wearing synthetic smart clothes. Perhaps I’ll darken my skin a little because I want to connect better with the person of colour I’m speaking with or because I know that company is trying to positively bias towards inclusive hires?

Then we face the ethical considerations of our choices as we curate as designers. Should I, as a white, middle-aged male, be adjusting the sliders of my “person generator” to make them a little more African American looking, even with the best of intentions? Do I know what those attribute should really be or will I rely on my own perception? Or how about a touch of biracial or gender-ambiguity in there so that the website might appeal to a certain target audience?

How about adjusting the GAN so that it generates different racial looks based on the geolocation of the user? Just writing those sentences feels loaded and dangerous, but it’s easy to start slipping down that slope, particularly as each shift becomes culturally normalised.

Some of this already exists, of course. But there are many important design questions to ask and decisions to be made here. For example, is any of this okay or just those things that are socially positive? What’s the ethical difference between blurring the background and a fake background? Who should decide what social good is and on what basis or experience? As mentioned before, should the person I’m talking to be made aware of it in the same way video conferencing apps do when they are being recorded? If so, how much? A list of everything that is synthetic or just a certain threshold?

My face is not actually altered here. I’m just making a stupid smile, but how would we know?

When it comes to other tools and apps, is it okay to run an AI-filter on all my Instagram posts to delete my ex-girlfriend? Perhaps it is an option when I change my relationship status on Facebook? Should other people seeing that photo be informed that it is doctored? Or should people be warned by the algorithms before they post, as with Instagram’s “anti-bullying” feature?

You can be sure someone is thinking of a tool to remove your ex from all your social media photos

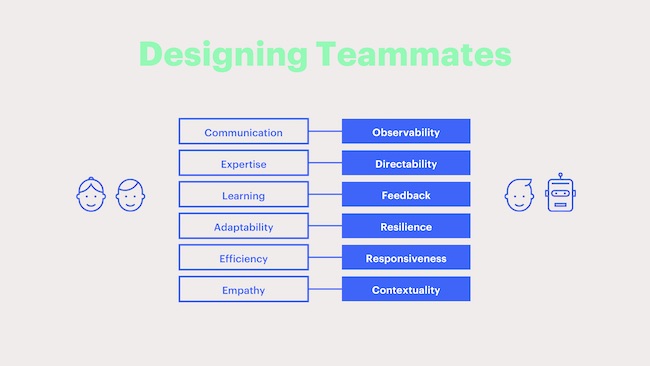

My colleague Connor Upton from Fjord at Accenture’s The Dock has been working together with his team to think about what they call Human-Centaur systems. These combine the best of human attributes with the best that AI offers in order to enhance each other. In order to achieve that, they’ve been examining what makes for a good colleague in the first place. Collaborative colleagues have:

- Communication

- Expertise

- Learning

- Adaptability

- Efficiency

- Empathy

The design challenge, then, is to embed these attributes into AI systems.

Since the AI systems are opaque, it means that things like “communication” become “observability.” The full list they suggest is:

- Observability

- Directability

- Feedback

- Resilience

- Responsiveness

- Contextuality

Thoughts on the future

Prediction is a fool’s game, so what follows are some thoughts about the possible ramifications of all that I’ve discussed. I do not doubt that they may seem ridiculous when we look back on them, but I’ve had my moments predicting mobile spam, the shift in privacy and the changes facing telcos, so here goes.

1. Photography and fashion

The bread-and-butter photography for fashion catalogues seems destined to be replaced by AI pretty quickly. The effort and expense will soon be outweighed by the convenience and personalisation that synthetic fashion offers.

This will mean that photography, like painting before it, carries on its twin vectors of being a niche, highbrow, artistic medium as well as an everyday activity now that we all have high-resolution camera in our pockets. It’s unlikely that the likes of Vogue will ditch models completely, but real, live supermodels may become even more exotic after we’ve got over the idea of synthetic ones being exotic. The bulk of anonymous models we see in ads and marketing materials will be synthetically generated and with them the sylists, make-up artists, photographers and studios.

Stock photography will almost certain go a similar way, given the ability to generate images from text phrases. Photography may shift towards photographers building up catalogues of material for training datasets rather than stock photos. Unlike stock photography, diverse and ambiguous images will be valuable, since they help train the neural networks more rigorously. There will probably be a market for dataset correction photography, in which sets of images are commissioned to rebalance skewed training data.

Of course the closed loop in all this is how AI is already changing the nature of photography.

Forensics may become of such importance that it becomes illegal to sell a camera that doesn’t have a unique, non-removable digital fingerprint, along with all the privacy uproar that will provoke.

2. Designers’ AI assistants will be valuable assets

In much the same way that a developer’s library is part of their value (and why Github accounts are often part of their resumés), designers may start to bring their trained AI-assistant with them as part of their toolkit. This may be in the form of trained neural networks, curated for a certain stylistic fingerprint. It may be that this really is some kind of AI-assistant with which (whom?) the designer has built up a working rapport and their human decisions are inextricably entwined with those of the AI.

We’re already seeing this in the community building up around Runway ML, a new tool that combines the power of machine learning with an elegant interface. It is able to interact with other apps, such as Figma, so that people can build workflows and plug-ins.

Generating faces with Runway ML

This will raise the issue of IP ownership. Does the designer who has trained a neural-network during their tenure at a company get to take that with them or does the IP belong to the employer? At present, the latter is most likely, but what if nobody else can work with it the same way as that individual? Does it still have the same value? Or should it all be open-source to avoid the issue all together? Many agencies still work in a black box mode, in which their creative chops are their secret source. Or maybe the IP will belong to the AI.

An alternative argument is that the IP belongs to the original developers of the algorithms, as has been made in the case of the AI-generated picture, Edmond de Belamy, which sold for $432,000 at Christie’s.

3. UX and UI design scale up

As mentioned earlier in this essay, the fields of UI and UX could profit enormously from large-scale multivariate testing generated and evaluated by AI. Workflows that move from sketch or even text descriptions to prototype code in a couple of steps may transform the field as much as platforms and applications like InVision, Sketch and Zeplin have in the past few years.

The perennial promise of automation is that it frees up the time, in this case for human designers to think more deeply and mindfully about their work. If the past decade is any indication, it seems more likely to increase the pace at which everyone sprints towards oblivion. Or perhaps the counter-movement towards more peaceful and thoughtful technology will flourish.

Either way, the skills of the digital designer (to use an awful phrase that nevertheless encompasses UX, UI, digital product design, and more) will need to include the ability to at least understand AI systems and work with them and with those who develop them, fuelling another decade of “should designers learn to code?” debates.

4. Synthetic Twins

Finally, the never-ending rise of privacy, data capture and surveillance state concerns may give rise to synthetic twins. Digital twins are in silica models of products, processes, services and even cities for testing, analysis and measurement. But as we’ve seen, a synthetic persona can happily inhabit online media as much as a real person.

Instead of trying to completely hide online, we may all opt for a synthetic twin, like the Chinese news anchors, to be our online public presence for us, while we keep private Finsta accounts for our real friends. At first, the public avatar might be controlled by us as the puppeteer, like the Chinese blogger recently unmasked by a technical glitch, but once it has gained enough of our personality, we might let the AI take over. It will be far more capable of providing interference to other AI-controlled surveillance systems.

Eventually, we might use some of its features in real-life prosthetics to avoid detection and capture in public spaces. This will open up a whole new market for creative synthetic persona designers.

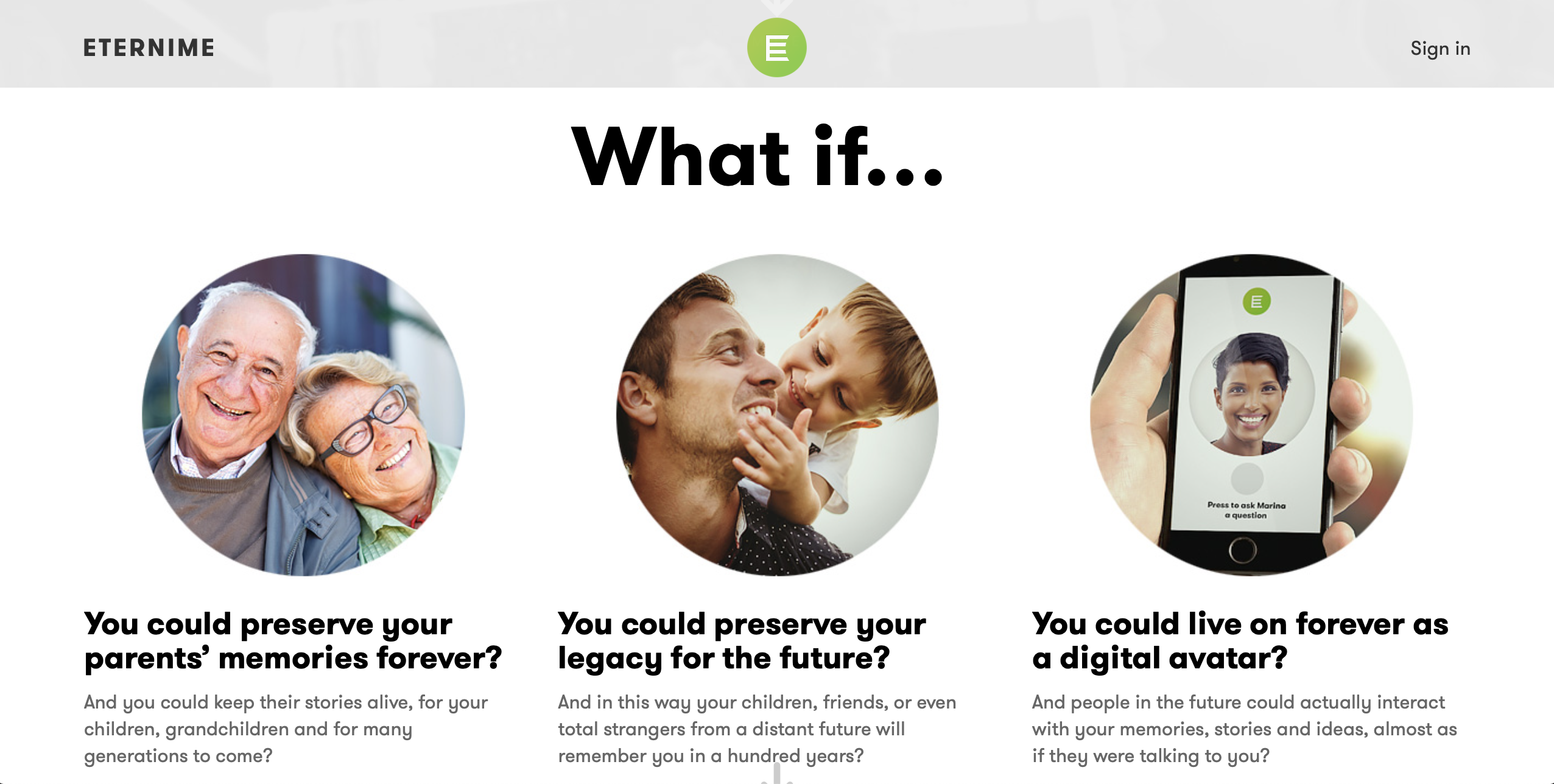

This sounds like an episode of Black Mirror until you consider that avatars are as old as the Internet. Meanwhile, work on encoding your social media personality for posterity in a digital afterlife is already well advanced with the likes of Lifnaut, Replika and Eterni.me. Casey Newton wrote a moving account of the virtual resurrection of Eugenia Kuyda’s closest friend, Roman Mazurenko back in 2016.

It is a short step to connect your captured persona with a high-definition 3D scan of yourself. Having made that investment, why would you wait until you die to use it? It may start as a luxury for the rich and famous, but it is likely to quickly filter down into the mainstream. The wealthy may have the most detailed synthetic twins and actually try to fake their real selves, but like all avatars, they’ll soon morph into custom, outlandish versions. Science fiction is filled with these scenarios.

Way past real

The intent of this survey of the technology was to show how far we already are and how close many of these technologies are to converging. FaceApp and Zao showed just how quickly novel technologies can enter the mainstream. As Steven Johnson argued in his book, Wonderland, it is play and entertainment that is most often the instigator of technological innovation throughout history.

What we consider reality—and certainly much of the media we consume—is already more synthetic that we realise. We just need our minds to catch up.

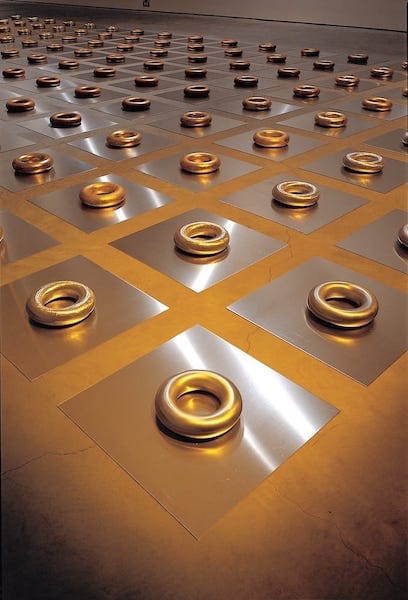

We may find that our value judgements of what is real and what is fake are not as solid as they seem. One of my favourite pieces of work exploring this is Way Past Real by jeweller and artist, Susan Cohn. For the installation, she placed a pure gold version of one of her doughnut bracelets amongst 152 others that looked almost identical, but some were anodised aluminium, others lit to look like what we think gold should look like. Despite Cohn pointing the real one out to me several times, I’ve frequently forgotten and consistently guessed wrong over the years. The real one doesn’t match my mental model—my internal story—of pure gold.

Way Past Real by Susan Cohn. Photo: John Gollings. Used with permission.

The spectre of the post-truth era is not driven by imaging technology. It is driven by storytelling supported by media. The most dangerous swap in the recent culture wars has not been faces, but the burden of proof. We no longer have to prove things are fake. We now have to try and prove that they are true. That is an existential question that has plagued philosophers for millennia.

Where are ethics situated?

Looking back through the history of digital image manipulation, intent is central to the discussion. Ethics are—and have always been—subject to a sliding scale of cultural norms. Jan Adkins, associate art director at National Geographic, explained in a 1989 article by J.D. Lasica:

“At the beginning of our access to Scitex, I think we were seduced by the dictum, ‘If it can be done, it must be done.’ If there was a soda can next to a bench in a contemplative park scene, we would remove the can digitally.

“But there’s a danger there. When a photograph becomes synthesis, fantasy, rather than reportage, then the whole purpose of the photograph dies. A photographer is a reporter — a photon thief, if you will. He goes and takes, with a delicate instrument, an extremely thin slice of life. When we changed that slice of life, no matter in what small way, we diluted our credibility. If images are altered to suit the editorial purposes of anyone, if soda cans or clutter or blacks or people of ethnic backgrounds are taken out, suddenly you’ve got a world that’s not only unreal but surreal.

Lasica’s 1989 article worries about the future ethics of manipulated images in print and TV. It is a fascinating read, because almost all of his What If? scenarios (TV and print news image manipulation, re-creation of actors, the demise of confidence in photographs-as-truth) have come to pass in the 30 years since it was written.

“You’ve got to rely on people’s ethics,” says Brian Steffans, graphics editor at The Los Angeles Times. “That’s not much different from relying on the reporter’s words. You don’t cheat just because the technology is available. Machines aren’t ethical or unethical — people are.”

The question is whether this is still true in the age of synthetic realities. Like any child learning from its parents, AI dutifully duplicates our biases and ethics.

Right now, tools like Runway ML are the equivalents of Photoshop 1.0. or early 3D applications. Runway ML is structured to access open source libraries and models and allow designers to create their own workflows. As designers and creative technologists start using these tools, the feedback loop between data scientists, developers and designers will become more rapid. Synthetic reality applications will change the creative industries just as much as Photoshop and 3D rendering did and it will happen far quicker.

Ethics is not about finding final answers, but constant questioning as new scenarios arise. Speed can too often sacrifice this reflection time. It’s crucial that we experiment, but equally critical that we make the time to consider the implications of what we have created.

Coda

If you are now feeling frazzled and suspicious of all media, I’ll leave you with some amazing footage from the 1890s. A golden age when the footage shot could be believed. Or could it?

MoMA’s The IMAX of the 1890s – How to see the first movies

This article was also published on Medium