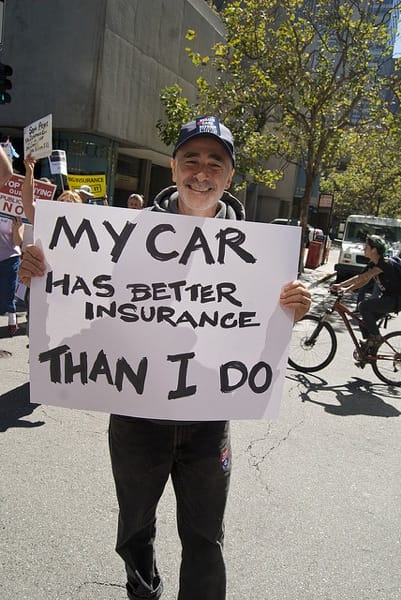

(Photo: Steve Rhodes)

I have a friend whose father used to be an insurance underwriter and he used to always complain about people lying about their insurance claims. He made the quite reasonable point that false claims put up the price of premiums for everyone. The problem is that insurance is often sold as a product rather than what it is, a service. When you pay your premium, it feels like you don’t get anything in return unless you claim. So the all-you-can-eat buffet effect comes into play – if you have paid a premium, when people do claim, they want to get their money’s worth.

Most people also have very little idea about what they are actually insured for an what they or not and routinely don’t claim for things they may well be insured for (broken spectacles, for example) and are often under-insured for their household contents. In our upcoming book on service design we use live|work’s work with Gjensidige as an example of re-thinking both the business model and the way complexity is presented. Although most people say they base their decisions on the policy, live|work found that actually people base their decision on price, because it’s the only thing they can compare policies on.

But there’s another aspect that is important to consider. Gjensidige, like all insurance companies, have complex actuary tables that calculate risk probabilities and thus the price. Most insurance companies follow similar models – household contents, life insurance, car insurance, etc., but there are, of course, many ways to slice and dice probabilities and risk. In the book we hope to present (we’re still clearing it with Gjensidige) a radically simpler version of insurance that came not from the service designers, but one of the actuaries who had been working on a formula for five years.

Edward de Bono’s book, Simplicity

Many service industries, such as mobility, finance, insurance and telecommunications have inherent complexity, but they often choose to present this to the customer. I’ve lost count of the number of ticket machines that have asked me what zone I want a ticket for or via which station I want to travel, when there is no information about these decisions to hand and, in any case, I don’t care and I’m in a hurry to catch a train. Similarly, even staff in a mobile phone shop struggle to navigate the telco tariffs. It’s no wonder than insurance comparison sites have become so popular.

What’s worse than presenting that internal complexity to customers? Ripping them off by not presenting it at all. Last week I received a letter from my car insurance company with the insurance premium for next year – 100 Euros more expensive than this year. Bear in mind that, in Germany, if you don’t cancel your insurance by the end of November, you’re automatically locked in for another year. Of course, I called to find out why and was very helpfully told that that’s an old tariff and that “new internal calculations” mean that my insurance would “only” go up by about 25 Euros.

The customer representative was only too happy to change me to that tariff, but now I’ve basically caught them lying. While on the one hand they’re extremely particular about claims, requiring recents, reports, etc., on the other hand they are quite happy not to inform me about new price structures or to explain the recalculation. So although the woman on the phone did the right thing, I now hate the insurance company for deliberately trying to get away with charging me more than is necessary.

Insurance is no exception. There are still many people paying rental fees to their telecoms companies for outdated or unused “equipment” (aka, telephones). The elderly are particularly prone to this because they tend not to shop around for deals in the same way and have a different relationship to technology. Thus that might not be aware that they’re paying 10 Euros a month for an old rotary dial phone when a DECT or even a corded phone might cost them just two or three times that monthly rental as a one-off payment. Banks do the same thing with outmoded accounts that attract high fees.

So, business as usual? Sadly yes, but it’s an unsustainable business model in the end. Service industries rely on ongoing relationships rather than one-off purchase, so it’s no good if your customers end up not trusting or, worse, hating you. It’s doubly damaging if your business relies on you having to trust your customers, as in the case of insurance. If you are a service, I expect you to be doing all you can to pass on your savings to me to stop me going somewhere else. Anything else and you’re selling what the Germans call Analog-Käse – fake cheese that looks, cooks and smells like cheese, but isn’t.